The Golden Piece: Armenia's Voskehat Grape

- By Gevorg Mnatsakanyan

- Translated by Hayk Khemchyan

- 21 April, 2022

Once addressed as Katvi Achk’ – Armenian for cat’s eye – for the brown freckles that dot its translucent berries, Voskehat has also been known as Kharji and Khach Kharji, though their meanings still elude the scientific community. For Boris Gasparyan, a wine researcher with Armenia’s Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, they could be said to refer to the Islamic practice of taxing its Christian populations with grapes.

A cluster of Voskehat | Photo Credit: Zenith Photo Studio / Tigran Hayrapetyan

A cluster of Voskehat | Photo Credit: Zenith Photo Studio / Tigran Hayrapetyan

“In Armenian, like in many of the languages to have impressed upon it over time, including Persian, Arabic, and Turkish, the word kharj signifies a tax, so it stands to reason that certain powers of the past might have claimed the fruit as a means to pay one’s dues,” says Gasparyan. He adds, “But this is for the linguists to figure out, not me.”

A progeny of the Eastern Vitis vinifera family found from Central Asia to the Armenian Highlands across the Iranian plateau, Voskehat’s exact date of birth is, as with the origin of some of its names, still unknown.

But excavations in the late 1940s at the ancient Urartian fortress of Teishebaini, today known as Karmir Blur or Red Hill, produced charred grape seeds thought to be morphologically similar to those of Voskehat, dating the cultivation of this variety as early as the 10th century BCE.

Charred grape seeds discovered at Karmir Blur thought to be morphologically similar to Voskehat | Photo Credit: Boris Gasparyan

Charred grape seeds discovered at Karmir Blur thought to be morphologically similar to Voskehat | Photo Credit: Boris Gasparyan

“Through radiocarbon dating, we have now shown beyond reasonable doubt that these seeds are a product of their time and not the loot of some enterprising mice from the future,” says Gasparyan, adding that further archaeobotanical and genetic analyses are needed to establish a definitive match between the old and new varieties of Voskehat.

Later digs of medieval sites deep inside the Kasagh gorge in Aragatsotn Province revealed similar finds, which together with an abundance of literary references from the late 19th century on, reassert Voskehat as a long-time sweetheart of the Armenian people.

Rise and Fall

As early as the 1880s, Voskehat was a major economic driver in the rich, volcanic soil of the foothills of the Ararat Plain, in and around what is today the town of Ashtarak. In 1945, the People’s Commissariat of Agriculture of Soviet Armenia estimated Voskehat to occupy more than 3,700 of the 171,000 acres taken up by the newly formed administrative district of Ashtarak.

It is around this time that Armenia’s communist winemakers used Voskehat to produce heavy wines in excess of 14 to 15 percent abv and with a pronounced bitterness. At its height, the Ashtarak brand of sherry-style wine made from Voskehat is said to have competed with the original Jerez of Spain, even as the grape served as the basic raw material for Armenia’s nascent sparkling wine industry.

But the chaos of sudden onset independence and hell-for-leather privatization of lands decimated acres of state-owned vineyards in the country. It failed to even spare the ancient gardens of Dalma in and around Yerevan, thought to be awash with olden vineyards of the indigenous grape.

Voskehat was then replaced with more neutral varieties like the Georgian Rkatsiteli and its hybrid progeny, Kangun, both of which require far less effort to cultivate. Individual growers and private vintners planted Voskehat at higher elevations in the Vayots Dzor Province, where an abundance of sunny days and relatively mild winters, coupled with the region's volcanic soil, proved sustainable.

The gorges of Vayots Dzor | Photo Credit: Zenith Photo Studio / Tigran Hayrapetyan

The gorges of Vayots Dzor | Photo Credit: Zenith Photo Studio / Tigran Hayrapetyan

Renaissance

Ever since Armenia’s vinicultural reawakening of the late 2000s, the region has emerged as a new wine country of sorts, attracting winemakers and investors from all over.

For the grape in Vayots Dzor, it adopts different aromas to better reflect the terroir of her new-found home–a bouquet that varies with each passing year.

With Vayots Dzor’s chillier winters, Voskehat’s wines can express aromas and flavors of peaches, and hints of apricot, while milder seasons can bring out more tropical notes. Be that as it may, Arman Manoukian, chief winemaker at WineWorks, a winery incubator based out of Yerevan, still prefers the Voskehat harvest of the foothills of Mount Aragats. “In my experience, you get more fragrant wines from these,” he says.

A late-ripening variety, bearing potent fruit only four to five years after planting, Voskehat is a grape that requires plenty of sun, water, and a great deal of hard work and care to reach full bloom. This could explain why early humans favored it in the region; the Ararat Valley offers 250 days of sun and 9.8 to 11.8 inches (250-300mm) of precipitation per year, and together with irrigation from the Araxes river, make ideal conditions for Voskehat.

Voskehat is also fragile. Voskehat is incredibly vulnerable to powdery mildew or oidium, which invades the densely packed clusters and from there, spreads havoc. Fending these off means hard work for cultivators.

But when all is said and done, working with Voskehat is nothing but pure pleasure, says Manoukian of WineWorks. “I don’t think of what I do as work. It’s a welcome pastime.”

Asked about the possible grafting of the Voskehat vine, Manoukian explains that the practice is foreign to the variety since it’s mainly homebred, but that such experiments are vital to its global dissemination and wider recognition. “People have already tried vaccinating Voskehat in France, Brazil, the US, and Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh), where the Armenian grape shares a spot with European varieties like Syrah and Pinot Noir in Khramort village,” he says.

Genetics

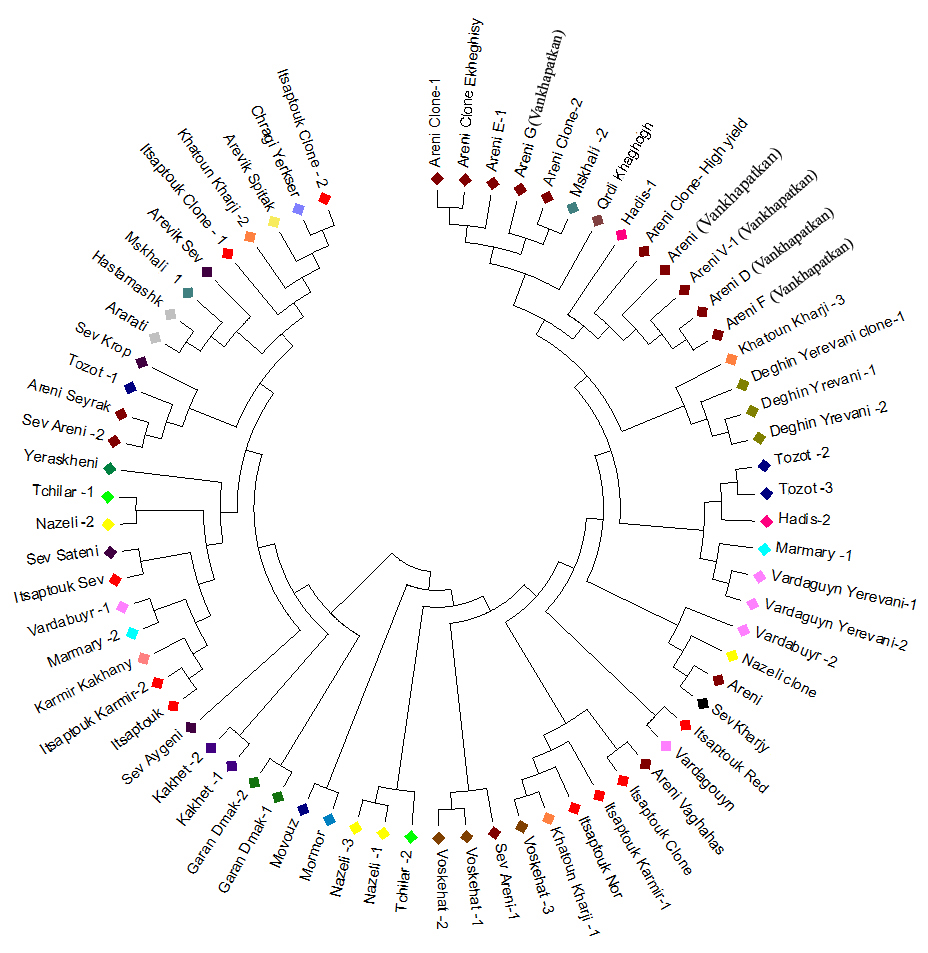

Historically, these kinds of relocations helped Voskehat find its 600-strong family of native varieties, to the extent that it has sometimes been confused with some of its more immediate kin, including Garan Dmak and Khatoun Kharji. But both ampelographic and genetic evidence have shown that there can be but one Voskehat.

Voskehat-3, for example, was identified as an imposter earlier in 2020 in a paper co-authored by Nelli Hovhannisyan, a researcher at the Department of Ecology and Nature Protection of Yerevan State University, and her colleagues. “Genetic analysis of the Voskhehat-3 grape from ampelographic vineyards on Armenia’s western border showed that its genotype was identical to the Khatoun Kharji-1 varietal, which means the latter was kept under the name Voskehat despite belonging to a different variety,” she says.

A dendrogram of the different varieties of Voskehat and its kin | Reprinted from Springer with permission from the authors.

A dendrogram of the different varieties of Voskehat and its kin | Reprinted from Springer with permission from the authors.

Appreciation

Such devotion to understanding Voskehat has yet to trickle down to the consumer level. Most still go with the brand rather than the grape when choosing their Armenian white, says Mariam Saghatelyan, partner at In Vino, the first of Armenia’s now many wine bars. To remedy the situation, she and her team of wine-trained waiters have set out on a mission to educate.

“Because wine can’t sell itself, service is everything in our case. It also means a lot of storytelling,” says Mariam. The stories are of the origins and meaning of Voskehat, of its terroir and wine styles, and of everything else that can help their customers make more informed decisions when picking out wines.

With foreign palates, it’s a process of familiarization through association, explains Saghatelyan. “The trick is to try and learn as much as you can about your customer’s preferences and then find a Voskehat that you think best suits these preferences. If they’re a New World Chardonnay kind of person, for example, an oaked Voskehat should sit nicely with them. Once initiated, they’ll be more open to experimenting with other Armenian wines.”

-

21 December, 2022

-

15 December, 2022

-

30 November, 2022

-

26 August, 2022

Similar Stories

-

21 April, 2022Rows of vineyards stretch along the fraught border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and now and then, they even take a bullet. For the community of Berdavan in the province of Tavush, 125 miles (200 km) from Yerevan, many inhabitants make their living exclusively off of these vineyards. Despite the unstable border and deadly crossfire, the vineyards are cultivated with care and what they yield is used to make quality wine.

21 April, 2022Rows of vineyards stretch along the fraught border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and now and then, they even take a bullet. For the community of Berdavan in the province of Tavush, 125 miles (200 km) from Yerevan, many inhabitants make their living exclusively off of these vineyards. Despite the unstable border and deadly crossfire, the vineyards are cultivated with care and what they yield is used to make quality wine. -

21 April, 2022On September 19th, 2020, a new restaurant opened its doors to customers in Yerevan. Katsin is unlike anything Yerevan has seen based on its size, comfort, menu, and service. Brothers Mher and Gevorg Adamyan conceived the concept, and by owning other cafés and restaurants around the city, have become leaders in the Armenian food scene.

21 April, 2022On September 19th, 2020, a new restaurant opened its doors to customers in Yerevan. Katsin is unlike anything Yerevan has seen based on its size, comfort, menu, and service. Brothers Mher and Gevorg Adamyan conceived the concept, and by owning other cafés and restaurants around the city, have become leaders in the Armenian food scene.